|

| Pro fisherman Ted Takasaki hoists a monster walleye he caught with the aid of modern sonar. Technology behind ‘depthfinders’ now includes side-imaging sonar, which Takasaki uses regularly in professional tournaments. The same advantages he finds can be yours, as you seek to make good use of limited fishing time. |

Sonar technology has come a long way since the early days. With all of the sport shows and new models coming, now is the time to research your electronics needs for spring.

Each baby step forward since the first consumer sonar appeared on store shelves has improved our understanding of how fish relate to structure and cover. This is all key information used by educated anglers to find and catch more fish.

But, sonar has made a quantum leap recently with the arrival of side imaging. With it, anglers can learn far more in less time about the layout of structure and find the subtle features that hold fish, whether it is inside turns and rock fingers, isolated boulders or weed patches. What once took days to discover– subtle features in a lake, river or reservoir– now takes just minutes.

“One sweep through an area and you can know exactly where and how everything lies beneath the water,” said Mark Gibson, global product manager for Humminbird. “That would take two hours with traditional, down-looking sonar. And, you can search shallow water.”

Gibson’s job is to listen to the needs of fishermen and work with engineers to get it done. His passion is bass fishing in Alabama, where the company’s factory is located. But, whether an angler is looking for bass, walleyes, crappies or other game fish, side imaging helps zero in on how fish are relating to structure and cover on a given day.

Just like other sonar technologies, we can thank the military for side imaging. Developed in the 1960s, its purpose was to track submarines. But, the U.S. Navy’s side imaging model required running a large torpedo-shaped transducer far behind the ship, which is hardly practical for fishing. Humminbird was able to adapt it by shrinking the transducer to six inches and finding a way to attach it to a boat.

|

| When manmade reservoirs are filled, all manner of stuff is forever under water. Here, with the Humminbird side-imaging sonar, we can clearly see a submerged swimming pool, with trees and a fallen tree beside it. |

Side imaging works something like MRI technology, a common medical procedure. A very thin beam of sound just one degree wide is shot to each side of the boat. The coverage area stretches nearly from the surface of the water to almost directly below the boat. In 50 feet of water, the beams can reach 360 feet to the sides, a distance greater than a football field. In 15 feet of water, the scan covers about 150 feet to each side. The unit pulses about 30 times each second, each time taking an image of a thin slice of the surrounding area.

Sophisticated microprocessors take the information and create a detailed video-like image. In one of Humminbird’s promotional photos of a side imaging sonar screen, a swimming pool submerged when an Alabama reservoir was formed is shown. In one corner, the steps leading down into the pool are clearly visible.

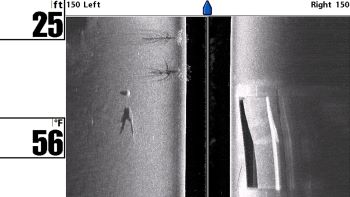

In another photo taken from an actual screen, the side image shows a rocky point with fish surrounding it.

Gibson recalls a time on the Mississippi River hunting walleyes on a wingdam. The side imaging showed exactly how the rocks were arranged and pinpointed small outcroppings that served as contact points for hungry walleyes.

|

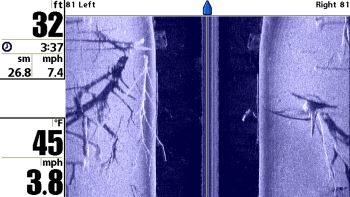

| Here we see an image of a fallen tree, captured by a Humminbird side-imaging sonar. Notice that you can see the split stump, and all the branches on the tree, representative of the kind of detail you can expect from these units. |

Yet another image shows a standing tree. Proving these sonars are true fish finders, the view shows both baitfish and predators so anglers can see how both were relating to structure, cover and each other.

Once a feature is located, the unit can be set to shoot to just one side of the boat to show more detail.

Imagine using a standard down-looking sonar over a rock pile. Slowly but surely, a view of the way it’s situated, how high it is and other features, such a weed patch or boulder, can be pictured. One pass with side imaging can reveal the same details. Pre-fishing for tournaments just got a lot easier. In addition to the pros utilizing it, side imaging is a great tool for anyone who wants to make the most of limited time on the water.

“Side imaging gives the complete picture of what’s underwater,” said Gibson. “Pros and serious recreational anglers see it and say, ‘I’ve got to have it.’”

Now, add a down-looking sonar and GPS with Navionics mapping. All of these images are displayed in color on a huge 7-inch diagonal screen, which is found on the Humminbird 900 series. Controls allow functions to be displayed one at a time or you can choose two of the three functions: GPS, side imaging, or down-looking sonar.

By combining GPS mapping with sonar functions, a detailed picture of the area can be created complete with waypoints that mark key structures and features.

As complicated as it sounds, operation is a breeze. The complete operational menu appears on one ‘page’ on the screen. Adjust the sensitivity to your liking. But, if things get out of whack, a simple click on the reset button takes the unit back to the factory defaults. The automatic settings were determined though consultation with professional anglers. These preset functions work well under most conditions.

Sonars with side imaging typically retail for about $2,000.

The Humminbird 700 series without side imaging offers an incredible 640 vertical pixel, high-resolution 5-inch diagonal screen that shows a traditional view looking down and stays bright no matter what the angle of view. The screen was manufactured for Humminbird by a company that does display screens for fighter jets.

Trouble in paradise

No matter how good your sonar is, its effectiveness can be sabotaged by poor installation.

With fiberglass boats, Gibson said one common problem comes when anglers mount their own transducers on the transom rather than shooting the signal through the hull. Transom-mounted transducers do well at low speeds, but air bubbles can foul the signal and therefore the image. Side imaging transducers do need to be installed on the outside in order to shoot out to the sides.

The speed of sound through fiberglass nearly matches the speed of sound through water, so the sonar can’t really tell the difference between the two substances. Very little signal power is lost as a result.

A problem can occur when the wrong epoxy is used to glue the transducer down, explained Gibson. Do not use a silicone product, and make certain the glue is slow-cured epoxy that takes more than an hour to cure. In addition, be sure to press down hard to remove any air bubbles in the glue.

Transom mounts are necessary with aluminum hulls. Gibson said his company supplies a template to help locate the transducer properly. Still, they can be installed at wrong angles.

Problems with the power source are another potential pitfall. Poor splicing of cords, or failure to solder connections (which exposes wires to the elements) can cause malfunctions, he says. Best advice with either hull – have a technician do it.

Advances in sonar technology, including side imaging, have created a tool that makes it easier to analyze structure and cover. The result is greater ability to find fish fast. Fish are running out of places to hide– but you still have to make ‘em bite. |