The muskellunge is one of the largest and most elusive fish that swims. A muskie will eat fish and sometimes ducklings and even small muskrats. It waits in weed beds and then lunges forward, clamping its large, tooth-lined jaws onto the prey. The muskie then gulps down the stunned or dead victim head first.

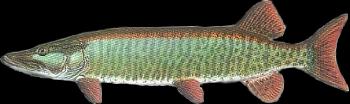

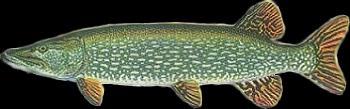

Muskies are light colored and usually have dark bars running up and down their long bodies. That’s the opposite of northern pike, which have light markings on a dark body. Muskies are silver, light green, or light brown. The foolproof way to tell a muskie from a northern is to count the pores on the underside of the jaw: A muskie has six or more. A northern has five or fewer.

Muskies are light colored and usually have dark bars running up and down their long bodies. That’s the opposite of northern pike, which have light markings on a dark body. Muskies are silver, light green, or light brown. The foolproof way to tell a muskie from a northern is to count the pores on the underside of the jaw: A muskie has six or more. A northern has five or fewer.

The muskie, unlike the northern pike, has six to nine pores (usually seven) on each side of the underside of the lower jaw. The lower half of the muskie’s cheek is not scaled. The lobes of the muskie’s tail are more pointed than those of the northern pike.

The muskie’s coloration, too, is distinct from a northern pike’s and takes three common forms that depend somewhat on the muskie’s place of origin, but all have a light background.

Muskies generally have three different variations; dark spots on a light background (spotted phase), dark bars on a light background (barred phase) and the third pattern, which is occasionally seen throughout Minnesota and Wisconsin, is the “clear” phase of light sides with no marks or very faint marks on the rear third of the fish.

MUSKELLUNGE: Clear Phase

Light Body Color & Pointed Tail Fins

MUSKELLUNGE: Barred Phase

Dark Markings, Light Backround & Pointed Tail Fins

MUSKELLUNGE: Spotted Phase

Dark Markings, Light Backround & Pointed Tail Fins

NORTHERN PIKE

The muskie spawns when the water temperature is 48 to 59 degrees, about two weeks later than the northern pike. A 40-pound female can produce more than 200,000 eggs. They generally spawn twice, the second time about 14 days after the first time. Unlike the northern pike’s adhesive eggs, which cling to vegetation, the muskie’s eggs settle to the bottom, rather than the weedy in-shore areas northern pike use. This separation of spawning areas apparently prevents northern pike fingerlings from preying on newly hatched muskie fry. In other circumstances, however, late-spawning northern pike have been observed actively spawning with muskie; the hybrid offspring is called a “tiger muskie.”

The muskie’s diet is similar to the northern pike’s. Fry eat plankton and then invertebrates but soon eat primarily fish. Muskie feeding peaks at water temperatures in the mid-60s and drops off as temperatures reach the mid-80s.

Muskie are smaller than northern pike during their first couple years but later grow longer and heavier than their relatives, occasionally surpassing 30 pounds. The average angler-caught muskie is much larger than the average northern pike. Genetics plays a role in this size difference. So do fishing regulations that protect muskie with a minimum-size limit but allow a liberal harvest of small to medium-size limit but allow a liberal harvest of small to medium-sized northern pike.

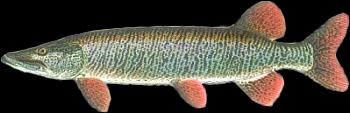

TIGER MUSKELLUNGE: (Hybrid)

Dark Markings, Light Backround

Rounded Tail Fins

The tiger muskie is the hybrid of the northern pike and muskie. It is usually infertile and has characteristics of both parents. The hybrid has distinct tiger bars on a light background, similar to the barred coloration pattern of some muskie. Its fins and tail lobes are rounded like a northern pike’s but colored like a muskie’s. The cheekscale and mandible-pore patterns are intermediate between a northern pike’s and muskie’s.

The tiger muskie grows slightly faster than either pure-strain parent in the first several years of life. It can exceed 30 pounds. Some tiger muskie occur naturally, though most hybrids are produced in hatcheries. They are useful in stocking because they grow quickly and endure high temperatures better than either paren does. Hybrids are easier to raise in a hatchery than pure-strain muskie, they reach legal size sooner and they are easier to catch. Because tiger muskie are usually sterile, their numbers can be controlled by changing the stocking rate.

Fish managers use the pure-strain muskie in lakes that can sustain naturally reproducing populations. The tiger muskie is reserved for lakes with heavy fishing pressure in and near the Twin Cities. Tiger muskie are subject to the same low possession limit and minimum-size limit that protect pure-strain muskie.

Muskie apparently have evolved to avoid head-on competition with northern pike. If northern pike find their way into muskie water, they seem to proliferate at the expense of muskies.

Muskie apparently have evolved to avoid head-on competition with northern pike. If northern pike find their way into muskie water, they seem to proliferate at the expense of muskies.

Why does the northern pike compete better? That question continues to puzzle fish biologist, though many believe that the earlier-hatching northern pike prey on newly hatched muskie if the two species use the same spawning areas.

In waters where muskie evolved without northern pike present, the muskie chooses the same weedy, flooded wetlands that serve as northern pike spawning areas elsewhere. If pike are introduced to these lakes, as they have been in Wisconsin drainages, the northern pike spawn in these same areas – but about two weeks earlier. So when the muskie fry hatch, they may be eaten by the larger young-of-the-year northern pike.

To make matters worse, young muskie routinely hang just below the surface of the water, where they are easy prey for birds from above or fish from below. Where the two species have coexisted for thousands of years, as they have in the Mississippi River headwaters, the muskie seem to have adopted different spawning areas. In Leech Lake, for example, muskie spawn offshore in 3 to 6 feet of water. Northern pike, meanwhile, use the weedy shorelines of bays and presumably have less chance to prey on the muskie.

Other evidence suggests that riverine conditions help muskie hold their own against northern pike, which prefer slower, weedier water. Researchers have speculated but haven’t proved that northern pike-muskie competition may be affected by other factors, including disease, dissolved oxygen concentrations, water-temperature fluctuations at spawning time, and prevailing water temperatures.

The muskie long has been recognized as special – a large, rare trophy. Its habitat requirements are more particular than that of its close relative, the northern pike. In many areas, the muskie’s existence is rather tenuous – threatened by fishing, habitat loss, and competition from other fish species. So the goal of muskie management is to create or protect self-sustaining populations and to produce a few large fish for the angler skilled and dedicated enough to catch them.

Habitat Protection

In lakes where the muskie is native, the protection of habitat – especially spawning areas – is the key to protecting these fish. Removal of shoreline and aquatic vegetation denies the muskie cover it needs. Eutrophication from farmland and residential development hurts spawning success by consuming oxygen along the riverbed or lake bottom, where the eggs of muskie and some forage fish incubate. Drainage of wetlands causes siltation and exaggerates the effects of flooding and drought – all to the detriment of muskie. Increased turbidity makes foraging harder for the sight-feeding muskie.

Stocking

Fisheries managers normally don’t stock muskie in lakes and rivers where they are native and self-sustaining. It simply isn’t necessary or effective. Stocking is used instead to create new muskie fisheries. Fisheries managers introduce muskie only to lakes that seem particularly well suited to them. An ideal lake has adequate forage, no chance of winterkill, suitable spawning areas and a size exceeding about 500 acres. Muskie then are stocked as fingerlings. If natural spawning areas are limited, stocking will continue on a regular schedule. Ideally, however, the population will become self-sustaining.

Fisheries managers have begun paying much more attention than they once did to the genetic origins of the muskie they stock. Several strains of the fish have evolved in different regions and watersheds. Some grow larger than others, which is of interest to the angler. More important, however, is that the adaptations of some strains allow them to better survive in certain habitats. For example, the muskie of Leech Lake and elsewhere in the upper Mississippi basin has evolved to coexist with northern pike, apparently by spawning in areas different from “classic” northern pike and muskie spawning habitat.

Efforts to stock muskies to control stunted panfish populations generally have failed. Muskies seem as ill-suited to the task as do northern pike. When muskies were introduced to one Wisconsin lake, the number of largemouth bass dropped. The number of yellow perch increased while their size decreased. Muskie actually appeared to contribute to the problem they were thought to correct. In another Wisconsin experiment, muskies were stocked in a lake filled with runty bluegill. Though the muskie fattened up quickly, the bluegill population showed no effect.

Trophy Management

Because muskie are perceived as trophies – and because large fish are scarce and old – most states impose a minimum-length limit and low possession limit.

Serious muskie fishermen are doing far more for their sport than the law requires, voluntarily releasing nearly all their fish, even those larger than the size limit, to be caught again. In the words of ichthyologist George C. Becker, “catch-and-release programs work by offering more fishing fun, and by providing the moral satisfaction that comes with leaving something for the next fisherman rather than contributing to the exhaustion of an already strained resource.”

No matter how lovingly we treat the muskellunges, it is destined to remain uncommon and hard to catch. Its biology guarantees that. With proper management, the occasional trophy will continue to thrill the dedicated muskie angler.

What is a trophy muskie?

- 50 inches or greater is a trophy female muskellunge.

(Most 50-inch muskellunge are 15 years or older.)- 45-49 inches is a trophy male muskellunge.

(Virtually no male muskellunge reach 50 inches in length.)

PROPER HANDLING & RELEASE

A big muskie is an old muskie. Females require 14 to 17 years to reach 30 pounds. Northern pike grow even more slowly. Once taken out of the water and hung on a wall or carved into fillets, a trophy is not soon replaced by another fish of its size. So, the key to creating trophy northern pike and muskie fishing is catch-and-release angling. Unfortunately, some fish are mortally injured by improper handling and cannot be successfully released.

All northern pike and muskie are difficult to handle because of their slippery hides (slime coat), lack of good handles and sharp teeth. Big fish are particularly troublesome because of their great size and power.

Careful handling makes catch-and-release work:

- The first step to successfully releasing fish is to use artificials rather than live bait. Caught on artificials and handled carefully, nearly all fish can be returned with no permanent injury.

- The second step is to keep the fish in the water if at all possible. If you must lift a big fish from the water, support as much of its body as possible to avoid injuring its internal organs.

- Never grip a fish by the eye sockets if you intend to release it. By doing so you abrade its eyes, injure the surrounding tissue and may cause blindness.

Here are some effective methods for handling large northern pike and muskie:

Hand release: Grip the fish over the back, right behind the gills (never by the eye sockets!) and hold it without squeezing it. With the other hand, use a pliers to remove the hooks, while leaving all but the head of the ;fish in the water. Sometimes hooks can be removed with the pliers only; the fish need never be touched.

Landing net: Hooks can be removed from some fish even as they remain in the net in the water. If that’s not possible, lift the fish aboard and remove the hooks while the fish is held behind the head and around the tail. To better restrain large fish, stretch a piece of cloth or plastic over the fish and pin it down as if it were in a straight jacket.

Stretcher: A stretcher is made of net or porous cloth about 2 to 3 feet wide stretched between two poles. As you draw the fish into the cradle and lift, the fold of the mesh supports and restrains the fish. This method requires two anglers.

Tailer: Developed by Atlantic salmon anglers, a tailer is a handle with a loop at one end that is slipped over the fish’s tail and tightened. The fish is thus securely held, though the head must be further restrained before the hooks are removed.